Paradoxically I begin this blog about Missions: Biblical Foundations and Contemporary Strategies, not with Chapter 1 on “The Biblical Narrative of Missions: Entering God Story” but with Chapter 13 about “The Missional Helix. Why? The Helix reflects the heart and soul of the book—the working DNA that stands behind its writing!

Perhaps a key word in the chapter is “discern”. We discern what God is saying to us in scripture during our present stage of life and ministry—a theological discernment so deep and personal that it transforms our hearts. We discern the cultural environment in which we live and minister. We discern the historical impulses that got us to the point that we are at. We discern practical strategies to convey God’s eternal message in contemporary, life-changing ways that build community and in so doing launch kingdom movements. Above all, we discern God’s working in our lives as He spiritually forms us in His Spirit to carry forward His mission. This discernment forms our character as disciples of Jesus and enables us to develop the competency for effective and exponential ministry.

Perhaps a key word in the chapter is “discern”. We discern what God is saying to us in scripture during our present stage of life and ministry—a theological discernment so deep and personal that it transforms our hearts. We discern the cultural environment in which we live and minister. We discern the historical impulses that got us to the point that we are at. We discern practical strategies to convey God’s eternal message in contemporary, life-changing ways that build community and in so doing launch kingdom movements. Above all, we discern God’s working in our lives as He spiritually forms us in His Spirit to carry forward His mission. This discernment forms our character as disciples of Jesus and enables us to develop the competency for effective and exponential ministry.

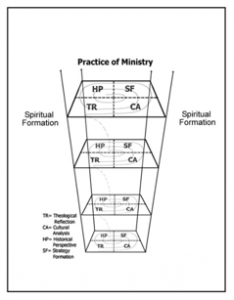

In other words, the Missional Helix is a spiral leading ministers to return time and time again to reflect theologically, culturally, historically, and strategically—within an environment of spiritual formation—to discern ministry models appropriate to a local context.

The Missional Helix was first developed when I saw the disparity, the friction between pragmatic church leaders using organizational principles and understandings to build what we typically call consumer churches and theologians in seminaries who sometimes reflected theologically but not out of experience in ministry and frequently without a passionate call for God’s mission in His world. This chapter begins with the story of Jim and Julie, who are learning from the seminary while ministering with their local church.

“They need to listen to and learn from each other,” Jim and Julie concluded. The purpose of the seminary is to serve the church. The church in turn should listen to people from the seminary with years of study and experience. Jim and Julie were learning equally from each environment: they were studying missions and ministry at the local seminary while ministering with youth in their local church.

“They noticed disparity in focus, contrasting orientations. People in the seminary focused on biblical and theological formation and the historical development of these theologies. They viewed pastoral and missional ministry as the practice of theology and, though they acknowledged the importance of these ministries, the hands-on aspects were ill-defined. Church leaders, on the other hand, tended to focus on pragmatics—asking about cultural relevance and success. They wanted to draw people to their church, shape the people’s lives, and make a major impact on the community.

“Jim and Julie had seen how easy it is for church leaders and missionaries, whether domestic or foreign, to make pragmatic plans without theological reflection. They recalled lessons learned earlier in their missions course, about moving from theology to practice in order to minister out of the will of God: ‘A theology of mission, like the rudder of a ship, guides the mission of God and provides direction,’ or it is ‘the engine of a ship, propelling forward the mission of God.’ They believed that a theology of mission is both a primary an ongoing activity in missionary practice. They remembered their friend Bill. After he had planted a church by seeking to meet the needs of the community, Bill perceived that the church had become more a vendor of goods and services than a community of the kingdom of God. Jim and Julie concurred that pragmatism without theological reflection threatens the future of the church. They were, however, thankful for ministry within a church where the Word of God was studied, disciple making was emphasized, and leaders were prayerfully seeking to live like Jesus.

“They heard church leaders claim that theologians are ivory-tower thinkers unable to connect with the common people and discerned truth in this statement. It is easy for people in the seminary to process intellectually without serving incarnationally. Recognizing this tendency, the organizers of the seminary curriculum asked entering students to read Helmut Thielicke’s classic book A Little Exercise for Young Theologians (1962) in the class introducing graduate studies. This book describes the cultural dislocation of seminary students who no longer speak the language of the common people. Jim and Julie were pleased, however, that almost all of their professors, especially those in missions and ministry, taught out of their ministries and experiences within local churches.

“They realized that they had the best of both worlds: a good seminary where they could learn deeply and a church community genuinely committed to faithfully following the way of God in Jesus Christ!” (pp. 307-308).

Thus the Missional Helix gives an integrative model of learning which brings together the strengths of studying in a seminary with those of ministering in a local church.

How have your experiences reflected those of Jim and Julie?

Dr. Gailyn Van Rheenen

Blog

Blog