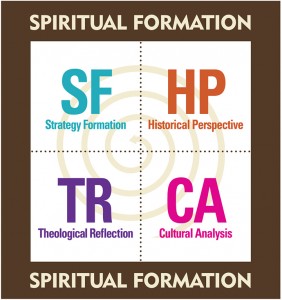

The previous missiological reflection described the Missional Helix and attempted to show the intertwining, inseparable nature of theological reflection, cultural analysis, historical perspective, and strategy formation within the context of spiritual formation. This blog describes the role of theology within the Missional Helix.

A theology of mission describes the heart and motivation of God and thereby defines the rationale for mission. It identifies what God is about in his world and why he is doing what he is doing. Christian ministers then are able to understand God’s purposes and discern God’s will for their lives. Reflecting on these theologies leads them to ask, “How do our lives and ministries reflect God?” or “How do we design patterns of life and models of ministry which reflect the kingdom of God?”

For example, a theology of mission is like the rudder of a ship which guides the mission of God and provides direction. My wife is fond of remembering how our children frequently wanted to “drive” when we took them on pedal boats. At times, they were so intent on pedaling—making the boat move—that they held the rudder in an extreme position, and we went in circles. Realizing their mistake but still intent on pedaling, they would move the rudder from one extreme to the other, so that we zigzagged across the lake. Without the foundation of a missional theology, Christian leaders likewise zigzag from fad to fad, from one theological perspective and related philosophies of ministry to another. A theology of mission, like the rudder of a ship, provides practical direction for Christian ministry.

For example, a theology of mission is like the rudder of a ship which guides the mission of God and provides direction. My wife is fond of remembering how our children frequently wanted to “drive” when we took them on pedal boats. At times, they were so intent on pedaling—making the boat move—that they held the rudder in an extreme position, and we went in circles. Realizing their mistake but still intent on pedaling, they would move the rudder from one extreme to the other, so that we zigzagged across the lake. Without the foundation of a missional theology, Christian leaders likewise zigzag from fad to fad, from one theological perspective and related philosophies of ministry to another. A theology of mission, like the rudder of a ship, provides practical direction for Christian ministry.

A theology of mission is also like the engine of a ship, propelling the mission of God forward. One spring, my wife and I taught at Abilene Christian University’s campus abroad program in Montevideo, Uruguay. During the semester, we traveled with our students to Iguazu Falls, a spectacular waterfall between Brazil and Argentina. One highlight of our visit was a motorboat excursion against the mighty current of the river almost to the foot of the falls. I was impressed not only by the immensity of the water’s flow but also by the power of the engine to push the boat up the river against the surge. A mission theology, like the engine of a ship, provides the power that enables finite humans to carry God’s infinite mission against the currents of popular cultures.

A theology of mission is also like the engine of a ship, propelling the mission of God forward. One spring, my wife and I taught at Abilene Christian University’s campus abroad program in Montevideo, Uruguay. During the semester, we traveled with our students to Iguazu Falls, a spectacular waterfall between Brazil and Argentina. One highlight of our visit was a motorboat excursion against the mighty current of the river almost to the foot of the falls. I was impressed not only by the immensity of the water’s flow but also by the power of the engine to push the boat up the river against the surge. A mission theology, like the engine of a ship, provides the power that enables finite humans to carry God’s infinite mission against the currents of popular cultures.

As these metaphors illustrate, theology is indispensable to the mission of God. A theology of mission provides both direction and empowerment for developing practices of missions.

Each of these four internal elements of the Missional Helix (theology, culture, history, and strategy) is essential in reflecting on and planning for Christian ministry. Theological reflection, however, is the beginning point for ministry formation and the most significant element within the internal structure of the spiral. In order to mirror the purposes and mind of God, all missiological decisions must be rooted both implicitly and explicitly in biblical theology.

Too many missionaries—while acknowledging the Bible as the Word of God—allow culture rather than Scripture to shape their core understandings of the church. The Bible is used to proof-text practice rather than to define the church’s essence. Lacking a biblically rooted ecclesiology, the teachings and practices of the church are likely to be shaped either implicitly by the dominant evangelical culture or explicitly by random surveys to ascertain what people want. A biblical understanding of the church’s nature enables missionaries to plant and nurture churches that are rooted in the mission of God rather than in presuppositions of popular culture.

The church today is reaping the harvest of its own cultural accommodation. I remember sitting in a congregational meeting 25 years ago when the words, “meeting felt needs,” were used 16 times in 30 minutes. Although these words expressed the need for Christian sensitivity, within them were also seeds of the slow demise of Christianity in North America. Cultural accommodation began to supersede living Christ-formed lives transformed into God’s image (2 Cor. 3:18).

The Missional Helix proposes that missionaries use Scripture to form a biblical understanding of the church. For instance, Paul, in Ephesians 2:19–22, uses multiple metaphors to describe the nature of the church. The church is a new nation: Christians are “no longer foreigners and strangers” but “fellow citizens” in a community of faith (v. 19). The church is a family, or God’s “household” (v. 19). The church is a holy temple, well constructed, with each part joined together and built around Jesus Christ, the chief cornerstone (vv. 20–22). This fellowship comes into existence through conversion: people dead in sin (2:1–3) have been made alive with Christ (vv. 4–7) by God’s grace (vv. 8–10). Paul stacks metaphors one on another to illustrate a redeemed fellowship brought together under Christ (1:3–11) and existing “for the praise of his glory” (v. 12). These perspectives form an inspired picture of God’s divine community.

The Missional Helix proposes that missionaries use Scripture to form a biblical understanding of the church. For instance, Paul, in Ephesians 2:19–22, uses multiple metaphors to describe the nature of the church. The church is a new nation: Christians are “no longer foreigners and strangers” but “fellow citizens” in a community of faith (v. 19). The church is a family, or God’s “household” (v. 19). The church is a holy temple, well constructed, with each part joined together and built around Jesus Christ, the chief cornerstone (vv. 20–22). This fellowship comes into existence through conversion: people dead in sin (2:1–3) have been made alive with Christ (vv. 4–7) by God’s grace (vv. 8–10). Paul stacks metaphors one on another to illustrate a redeemed fellowship brought together under Christ (1:3–11) and existing “for the praise of his glory” (v. 12). These perspectives form an inspired picture of God’s divine community.

Theological reflection, however, extends beyond textual study. Christian ministers must realize that all readers understand and apply Scripture within their historical traditions, based on their rational systems of thought, and formed by their experience. The missionary therefore must be cognizant of four resources that shape theological reflection: Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience (Stone and Duke 1996, 43–54). For example, in rural, face-to-face cultures, Christians tend to perceive the church as a “family”; in modern, industrial contexts, as a “business”; and in postmodern, informational cultures, as a “network,” or sometimes as a “community.” Missionaries and ministers, as theological “meaning makers,” must theologically reflect on the connotation of these metaphors, using all four resources.

Sources:

- Chapter 3 of Missions: Biblical Foundations and Contemporary Strategies on “Theological Foundations of Missions,” pp. 63-64.

- Chapter 13 of Missions: Biblical Foundations and Contemporary Strategies, on “The Missional Helix,” pp. 311-312

Previous Blogs on the Missional Helix:

Dr. Gailyn Van Rheenen, Facilitator of Church Planting and Renewal

Blog

Blog