Missions and the discipline of missiology are important because without missions there is no church. When missions goes into decline, so does the church. Missions is the lifeblood of the church.

The focus of missiology as a discipline is to equip disciples who walk with Jesus and who equip others to reflect the life and teaching of Jesus in maturing, faithful, reproducing communities of faith. As such, missiology entails five interactive disciplines as illustrated in “The Missional Helix.”1

Too frequently missiology is considered a pragmatic discipline developed around strategy. Missiology began to reflect the pragmatics of culture: church planting in the West, for example, often resembled starting a business with methodologies of attraction rather than making disciples who make disciples who make even more disciples. Over time, some churches increasingly reflect the world—with a business structure of full-time people administrating an organization—rather than a community of people on mission with God.

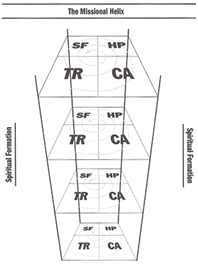

Missiology as a discipline and practice of life, however, is much deeper and more transformative. In the Missional Helix, the discipline reflects as least five interrelated elements: theological reflection (TR), cultural analysis (CA), historical perspective (HP), strategies formation (SF), and spiritual formation. In this helix, ministry formation is like a spiral. The coils turn round and round, passing through the same landmarks, but always at a slightly higher level. This spiral, a helix, is descriptive of a process of effective missionary ministry. Effective missionaries are sensitive to all five elements in their teaching and imitative practice.

Missiology as a discipline and practice of life, however, is much deeper and more transformative. In the Missional Helix, the discipline reflects as least five interrelated elements: theological reflection (TR), cultural analysis (CA), historical perspective (HP), strategies formation (SF), and spiritual formation. In this helix, ministry formation is like a spiral. The coils turn round and round, passing through the same landmarks, but always at a slightly higher level. This spiral, a helix, is descriptive of a process of effective missionary ministry. Effective missionaries are sensitive to all five elements in their teaching and imitative practice.

The spiral begins with theologies, such as the missio Dei, the kingdom of God, incarnation, and atonement—rooted in the narrative of the biblical text—which focus and form our perspectives of culture and practices of ministry. Cultural analysis enables missionaries and ministers to define types of peoples within cultural contexts—to understand the social construction of their reality, to perceive how they are socially related to one another, and to explain how the Christian message intersects with every aspect of culture (birth rites, coming of age rituals, weddings, funerals, and so on). The spiral proceeds to consider what has occurred historically in the missional context. Historical perspective narrates how things got to be as they are based upon the interrelated stories of the particular nation, tribe, lineage, neighborhood, the church, and God’s mission. Strategy formation helps shape the practical methodology of ministry. These contextual strategies draw deeply from cultural and historical understandings to theologically discern what God is saying about the practice of ministry and develop actual practices to implement them. Finally, this shaping of ministry takes place within the environment of spiritual formation as Christian servants humbly submit their lives to a covenant relationship with God as Father and enthrone Christ as their King as people of his kingdom.

The Relationship between the Five Elements of Ministry Formation

The missional helix is a spiral because the missionary returns time and time again to reflect theologically, culturally, historically, and strategically under the guiding hand of God to develop ministry models appropriate to the local context. Theology, social understandings, history of missions, and strategy all work together and interpenetrate each other. Thus praxis impacts theology, which in turn shapes the practice of ministry.

The missional helix is a spiral because the missionary returns time and time again to reflect theologically, culturally, historically, and strategically under the guiding hand of God to develop ministry models appropriate to the local context. Theology, social understandings, history of missions, and strategy all work together and interpenetrate each other. Thus praxis impacts theology, which in turn shapes the practice of ministry.

In this diagram, the broken line between the four internal elements of strategy formation demonstrates how each interacts with the others. In this process God is shaping who Christian leaders are and what they do within an environment of spiritual formation as they humbly and prayerfully submit to God as Father and to each other.

The diagram is a helix because theology, history, culture, and the practice of ministry build on one another as the community of faith collectively develops understandings and a vision of God’s will within their cultural context. Like a spring, the spiral grows to new heights as ministry understandings and experiences develop. Ideally the missionary is always learning, always spiraling, to a new level of understanding and competence.

The Components of the Missional Helix

Each of these four internal elements of the missional helix (theology, history, culture, and strategy) is essential in reflecting on and planning for Christian ministry.

Theological Reflection

Theological reflection is the beginning point for ministry formation and the most significant element within the internal structure of the spiral. All missiological decisions must be rooted both implicitly and explicitly in biblical theology in order to mirror the purposes and mind of God.

Too many missionaries, while acknowledging the Bible as the Word of God, allow culture rather than Scripture to shape their core understandings of the church. The Bible is used to proof-text practice rather than to define her essence. Without a biblically-rooted ecclesiology, the teachings and practices of the church are likely to be shaped either implicitly by the dominant evangelical culture or explicitly by random surveys to ascertain what people want. A biblical understanding of the nature of the church, consequently, enables missionaries to plant and nurture churches that are rooted in the mission of God rather than presuppositions of popular culture. As expressed earlier, the entrepreneurial spirit of North America induces church planters to begin churches that are organized and managed like a business rather than a community formed by the Lordship of Christ.

The missional helix proposes that missionaries use Scripture to form a biblical understanding of the church. Missionaries and ministers are, therefore, theological meaning makers. To be a missionary necessitates being a theologian!

Cultural Analysis

In addition to theological reflection, missionaries must undertake an in-depth worldview analysis of the local culture. Much too often, this second element of the Missional Helix is excluded. Ministers and church planters naively project their worldviews upon other contexts and interpret reality in terms of their heritage. This intellectual colonialism results in transplanted theologies, reflecting the missionaries’ heritage, rather than contextualized theologies, developed by reflecting on Scripture within the context of local languages, thought categories, and ritual patterns. Transplanted theologies are merely uprooted from one context and transferred to a new one with the expectation that the meanings will be the same in both cultures. The beginning point of theologizing in a new culture is always a thorough analysis of the culture on a worldview level. Based on these cultural understandings, trained missionaries are able to be theological brokers to those within the culture and minister alongside them in developing a local contextualized theology.

Frequently missionaries and church planters analyze bits and pieces of a culture but are unable to make a systematic cultural analysis. Or, they effectively analyze culture in broad, general terms, but are not equipped to make localized cultural analysis.

Effective missionaries, by their very nature, are practical cultural anthropologists.

Historical Perspective

Likewise, missionaries must develop ministry based upon historical perspective rather than being oblivious to what has previously occurred. Historical perspective provides many insights that guide missionaries to develop their practice of ministry. For example, the reading of history greatly aids contemporary evangelists to understand syncretism. Ancient Israel, like many people coming out of animism, was tempted to follow both God and the gods of the nations. “They bow[ed] down and [swore] by the Lord and . . . also by Molech” (Zeph 1:5). Some Modern Christians, for example, have syncretized secularism and theism by negating the Holy Spirit and demythologizing spiritual powers. Postmodern Christians have brought new syncretisms, including pervasive relativism, fascination with spiritual powers, focusing on power and neglecting truth, and interpreting emotions and intuition as the work of the Holy Spirit.

Missionaries will find it difficult to understand the nature of syncretism without historical perspective.

Because of their short national history and focus on practical inclinations, many North Americans sense the future without understanding the past. Samuel Escobar believes that North American missiologists tend to negate theory and historical background. In other words, they look at missions as a management task necessitating “a task-oriented sequence of steps to be followed in order to achieve” specified goals. He challenges the North American missions community to expand the horizons of their “managerial missiology.”2

Strategy Formation

Missions, by its very nature, necessitates strategic planning. Strategy formation, however, should never stand by itself as a self-contained, how-to-do-it prescription. Never should practitioners merely ask the question, “Does it work?” because many strategies that “create an impact,” enabling the church to grow for short periods of time, do not reflect the qualities and purposes of God. “Attractional,” “consumer” or “health-wealth” orientations, for example, produce numerical results, but when God takes away health or wealth as in the case of Job, the faith of those who have come to Christ to receive his “benefits” will likely prove deficient. A question that better reflects the Missional Helix is: Does this model of praxis guide people to become disciples of Jesus and people of his mission within this historical, cultural context?

The foundational understandings of theology and the perspectives developed through cultural analysis and historical perspective should, then, lead missionaries to critical reflection upon praxis. The missionary or minister should return time and time again to reflect theologically, culturally, historically, and strategically within the context of spiritual formation in order to develop ministry models that are appropriate to the local context. The four elements work together and interpenetrate each other. Based on these understandings, strategy is the practice of model formation for ministry shaped by theological reflection, cultural analysis, and historical perspective and by the continued practice of ministry while being spiritually formed as disciples of Christ.

Currently missions strategies are undergoing radical transformation as missiologists reflect upon the different social contexts of missions and the need for the church to be God’s distinct, called-out people. For example, the United States once considered itself to be a Christian nation. Many early immigrants fled Europe seeking religious freedom in the New World. As new towns emerged, churches occupied both a geographically and philosophically central location reflecting the church’s role in shaping cultural customs and values. New denominations emerged reflecting the new modern paradigms and flavors of the North American frontier.

The Christian church in the twenty-first century, however, has generally lost this privileged position in the United States and is now only one of many influences shaping contemporary culture. Nevertheless, many Christians assume that the USA is still a Christian nation and attempt to promote Christian morals and ethics through public political activity. This has caused outsiders to view the church as sheltered, judgmental, and anti-homosexual,3 a cynicism amplified by 81 percent of white evangelicals voting for Donald Trump in 2017 presidential election.4

Returning to England after thirty years of missionary work in India, Lesslie Newbigin, father of the contemporary missional movement, witnessed an even greater decline of Christianity in his country. In Foolishness to the Greeks, he asked “What would be involved in a missionary encounter between the gospel and this whole way of perceiving, thinking, and living that we call ‘modern Western culture’?” or in its shortened more popular form, “Can the West be converted?”5 This must also be a guiding question for us in North America during this generation. The church must learn to serve in pre-Constantinian ways as a minority—to survive from the margins rather than from the center of culture. “Missions, which have been accustomed to flowing down the current of world power, are now faced with the necessity of learning for the first time to swim against the current.”6

Spiritual Formation

The final and most important element of the Missional Helix is spiritual formation because it activates and shapes all the inward sectors of the helix.

Spiritual formation is defined by Paul as walking with God in such a way that we are being “transformed into his likeness with ever-increasing glory” (2 Cor 3:18). This glory is embodied in Christ who brought a new covenant which brings life enlivened by the Holy Spirit. This glory is contrasted with the fading glory of the old covenant of Moses, which was merely written on “tablets” or “letters” of stone (3:3, 7), not in human hearts. Paul says, “Will not the ministry of the Spirit be even more glorious? If the ministry that brought condemnation was glorious, how much more glorious is the ministry that brings righteousness!” (3:8–9).

Paul compares his ministry to that of Moses. Because of the hope embodied in new covenant, “we are very bold!” (3:12). When Moses came down from Mt. Sinai, his countenance so reflected the radiance of God that the Israelites were not able to look at him. Moses, however, put a veil over his face to hide this “fading glory” (3:13). Paul testifies that he and all other Christians who live minister with “unveiled” faces who have turned to the Lord are being transformed “into his likeness” by the Holy Spirit (3:18). As light permeates darkness, Paul’s message gains credibility because of the presence of the Holy Spirit working powerfully within the church.

May we be people of unveiled faces boldly reflecting God’s glory as we are transformed into his likeness by the Holy Spirit!

The twin themes of covenant and kingdom reverberate throughout the Bible and define the essence of spiritual formation. Covenant signifies the personal, intimate relationship of God with his people. Kingdom reflects God’s rule with authority and power among his people. From this perspective, spiritual formation is the shaping of ministry as Christian servants humbly submit their lives to a covenant relationship with God as Father and enthrone Christ as their King as people of his kingdom.

Case Study

To read the application the Missional Helix to a particular missions class, Communicating Christ in Animistic Contexts, read this related article: http://missiology.com/blog/The-Missional-Helix-in-Teaching-and-Ministry-A-Case-Study.

Notes

1 The Missional Helix is the integrative paradigm of Van Rheenen’s Missions: Biblical Foundations and Contemporary Strategies, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2014), ch. 13. Chapters 1, 3, and 4 focus on theological reflection, ch. 8 on historical reflection, chs. 9–12 on cultural analysis; chs. 14–16 of strategy formation; and chs. 2, 5, and 7 on spiritual formation.

2 Samuel Escobar, Home Grown Leaders (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 1992, 13–14); cf. idem “Evangelical Missiology: Peering into the Future at the Turn of the Century” in Global Missiology for the 21st Century: The Iguassu Dialogue, ed. William D. Taylor (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2000), 109–12.

3 David Kinnaman, UnChristian: What a New Generation Really Thinks about Christianity . . . and Why It Matters (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2007), 21–40.

4 Myriam Renaud, “Myths Debunked: Why Did White Evangelical Christians Vote for Trump?” University of Chicago Divinity School, January 19, 2017, https://divinity.uchicago.edu/sightings/myths-debunked-why-did-white-evangelical-christians-vote-trump.

5 Lesslie Newbigin, Foolishness to the Greeks: The Gospel and Western Culture (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1986), 1.

6 Lesslie Newbigin, The Gospel in Pluralistic Society (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), 8.

Dr. Gailyn Van Rheenen served as a church-planting missionary to East Africa for 14 years, taught Missions and Evangelism at Abilene Christian University for 18 years, and is the founder and currently a facilitator of church planting and renewal within Mission Alive (www.missionalive.org). The second edition of his book Missions: Biblical Foundations and Contemporary Strategies was published by Zondervan/Harper Collins in 2014. Other publications include Communicating Christ in Animistic Contexts (William Carey Library) and The Changing Face of World Missions (Baker Academic; authored with Michael Pocock and Doug McConnell).

Dr. Gailyn Van Rheenen served as a church-planting missionary to East Africa for 14 years, taught Missions and Evangelism at Abilene Christian University for 18 years, and is the founder and currently a facilitator of church planting and renewal within Mission Alive (www.missionalive.org). The second edition of his book Missions: Biblical Foundations and Contemporary Strategies was published by Zondervan/Harper Collins in 2014. Other publications include Communicating Christ in Animistic Contexts (William Carey Library) and The Changing Face of World Missions (Baker Academic; authored with Michael Pocock and Doug McConnell).

Blog

Blog